After the lengthy discussion of the construction V+Vsubjunctive in Mark 10:36, I thought it would be worthwhile to look at some possible paths of development for the variation we find in Mark 10:36. What I want to demonstrate here is the high value that a broader knowledge of the Greek language and its history can provide.

The variants are*:

| τί θέλετέ [με] ποιήσω ὑμῖν; | אc B Ψ |

| τί θέλετέ ποιήσω ὑμῖν; | C f1 f13 Θ 205 565 |

| Ποιήσω ὑμῖν; | D |

| τί θέλετέ ἵνα ποιήσω ὑμῖν; | 1241 |

| τί θέλετέ ποιῆσαί με ὑμῖν; | A Majority Text |

| τί θέλετέ με ποιῆσαί ὑμῖν; | אc2 L Wc 579 892 2427 |

| τί θέλετέ ποιῆσαί ὑμῖν; | W* Δ |

* א* lacks the entire line as a result of homoioteleuton from the θέλομεν of v. 25 35 through ἵνα of v.37. The variants and the manuscripts listed are taken from the apparatuses of Tischendorf and the UBS4.

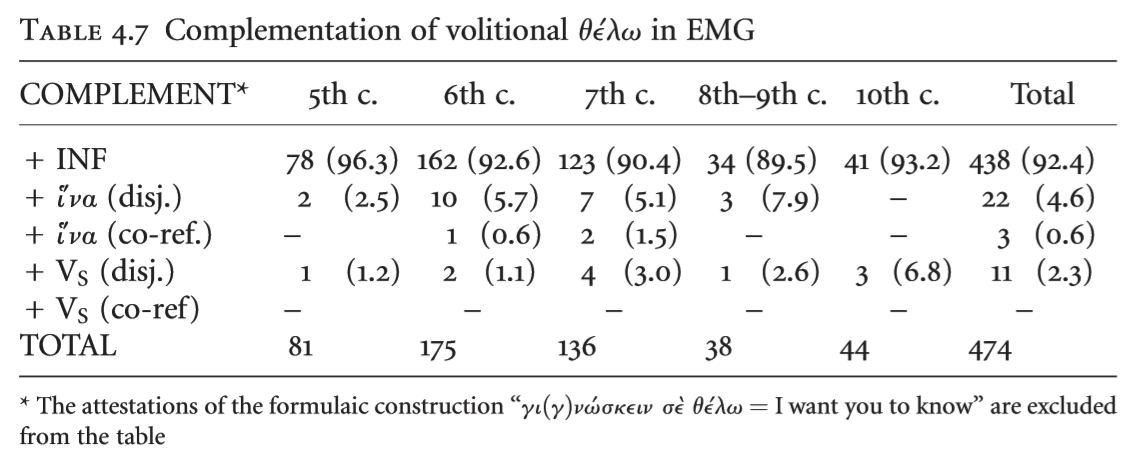

The last two are the most common in the majority text. And while for some people that’s enough for a reading to be original, that simply doesn’t work here. The change from the infinitive of the majority text to the subjunctive (particularly a subjunctive without ἵνα) is the most improbable change there could be. The earliest witness we have are all from the 4th century and they all vary in what they provide as a text. According to the data put forward by Markopoulos, the farther we get from the Hellenistic period, them more likely that the bare subjunctive will be replaced by some other construction. He provides this useful chart for how the distribution of different construction patterns change from the Hellenistic period to the Early Medieval period, which I include below with his own commentary on it (Markopoulos 2009, 104-105):

Table 4.7 is illuminating in two respects: on the one hand, it depicts convincingly the domination of the Infinitive as the mean means of complementation of θέλω. On the other hand, it shows that clausal complementation is gaining ground, not really relative to the Infinitive but to the third alternative, the Verbal complement in the Subjunctive, which is still undoubtedly extant, but less frequent now than the ἵνα–clause (cf. Fig 4.2).

Now, with this in mind, recall R. T. France’s comments on this textual issue:

“The syntactically impossible reading of א B, τί θέλετέ με ποιήσω, must result from a conflation of the two constructions. The reading which best explains the variants is τί θέλετε ποιήσω (with ἵνα understood), the abruptness of which led to correcting the subjunctive to an infinitive, with the consequent addition of με” (R. T. France 2002).

France’s proposal essentially necessitates the following path of development:

τί θέλετέ ποιήσω ὑμῖν; (C f1 f13 Θ 205 565)

–> τί θέλετέ ποιῆσαί ὑμῖν; (W* Δ)

–> τί θέλετέ με ποιῆσαί ὑμῖν; (אc2 L Wc 579 892 2427)

–> τί θέλετέ με ποιήσω ὑμῖν; (אc B Ψ arm)

This line of textual development necessitates that France is correct about the construction being “abrupt.” But the data suggests that it probably isn’t. More likely this is a perfectly normal construction that is substantially more common in the everyday speech of Greek speakers that has on various occasions through the history of the language slipped into the literary language—notably only in speeches and dialogue. From there, France (Holmes, among others) would have us believe that the second corrector of Sinaiticus (6th-7th c.) had a superior text to the original corrector (4th c.)while that same original corrector agrees perfectly perfectly with Vaticanus. It seems to me that this line of reasoning takes the impossibility of the reading as its starting point. But we already know now that it isn’t impossible. It is, in fact, quite natural.

We also know from Markopoulos’ table above that the V + Vsubjunctive construction begins to die in Early Medieval Greek—around the same time that Sinaiticus’ second group of correctors work to bring the text in line with the Byzantine tradition. At that point in time, the infinitive reading had already been introduced (as evidenced by Alexandrinus) and it’s consistently looking more and more appealing to those scribes. On top of that, the more rare this construction gets, the less acceptable to scribes the additional με appears. In response, some scribes change the subjunctive to an infinitive and other scribes just drop out the pronoun.

On this account, accepting the reading of the NA27 allows for deriving most of the variants directly rather than relying of an incredibly complex line of derivation as the one that France proposes. At least, that’s how I see it, but I’m not a text critic. I’m a linguist who dabbles in it from time to time. I would be curious about anyone else’s thoughts on this proposed reconstruction.

Works cited

France, R. T. 2002. The Gospel of Mark. New International Greek Testament Commentary. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

Markopoulos, Theodore. 2009. The Future in Greek: From Ancient to Medieval. Oxford: Oxford University Press.