My copy of the Cambridge Grammar of Classical Greek arrived in the mail last week. Since then I have had the pleasure of perusing roughly 100 pages of it, not a close and in-depth reading, but at the very least a survey of topics that most interest me.

The physical quality of the book is, at best, middling. Gone, I think, are the days where we can expect, even the more expensive hardcover, to be produced with a good Smyth sewn binding that will stand the test of time and use. The hardcover that I have is a flat-cut and glued textblock. It is, of course, case-bound and, for what it is, lays surprisingly flat. I would be hesitant to recommend the extra cost for the hardcover.

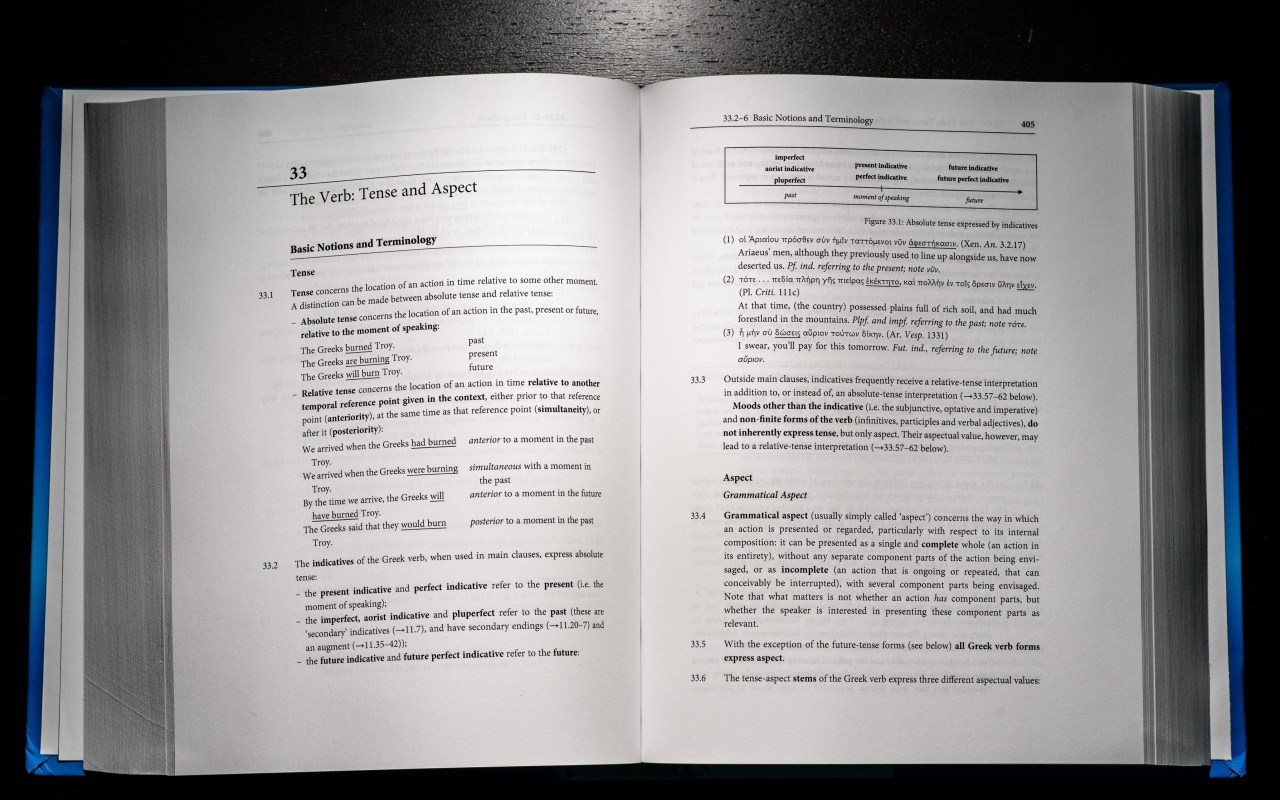

The internals, however, deserve much more praise. The book is quite large in all dimension. As a result, the page layout is lovely, with substantial margins and plenty of space for well-formatted examples. For a given topic, the relevant elements of the example are underlined in the Greek text, but not in the corresponding English translation. Grammatical glossing is provided for the relevant Greek, as well, in italics following the English free translation. No other grammatical glossing is provided. This is not ideal for typologists, but it is a step above all past reference grammars. The grammar is reasonably usable for those working in cross-linguistic comparison. Though these sorts of priorities are things that many classicists and biblical scholars seem uninterested in understanding, I think the editors, in their presentional decisions, illustrate some understanding of the importance making their work accessible for comparative linguistic work.

The prose is clear, and the description avoids unnecessary linguistic jargon. These are of particular importance for the long-term staying power of a reference grammar: if the linguistic framework adopted is no longer comprehensible 25 years from now, the description itself risks also becoming incomprehensible as well. References are limited to the fairly extensive bibliographies at the end. There is no regular engagement with the secondary literature in the body of the work. While some might find this an unusual decision, it is actually extremely common for how reference grammars are laid out and organized.

A minority of NT scholars and students will likely be disappointed to find that the authors take the position that tense is grammaticalized in the indicative mood, but of course grammarians and linguists of Classical Greek have wholly rejected the idea of a tenseless verb for the language on empirical ground. Overall, the chapters on tense and aspect, which I have read through, are well-structured, with clear example sentences and accurate descriptions that have practical and accessible definitions of technical terminology. Similarly, the chapter on voice alternations is a dramatic improvement over all other current reference grammars available in English, though it would have been nice if more discussion of transitivity was included.

Overall, I eagerly look forward to digging deeper into this excellent looking volume. In the coming weeks, I am curious to see how they describe the pronominal system, especially. But summarily, I can confidently say van Emde Boas, Rijksbaron, Huitink, and de Bakker’s new grammar deserves to be on any serious Ancient Greek scholar’s shelf. And its low paper back price makes it an extremely easy decision.