One thing students of Koine should do more is read and translate non-biblical papyri. If there is one practice that will sabotage your sense of arrival as a student, it is reading legal documents about loans that transpired between farmers and soldiers in places like Krokodilonpolis (Crocodile City) in 105 BC. Unlike the Bible, you’ve never seen it before in translation. You have nothing to rely on except pure competence in Koine. If you cannot read papyri well, it is likely because your knowledge of Koine is not as strong as you thought it was. Don’t let this discourage you. It is an invitation to grow. When we limit ourselves to the New Testament, we gain confidence, but this confidence is not our friend. This is why reading the Hebrew Bible for knowledge of Hebrew is superior to reading the New Testament for Greek: few if any of us have memorized the sweeping narratives of 1-2 Samuel. When we read in Hebrew, we usually have nothing but our competence to guide us. In fact, I suspect that many who complain Hebrew is harder than Greek are simply experiencing learning without the crutch of memory.

The same is not true of reading the New Testament. You should never mistake ability to read the New Testament for proficiency in Koine Greek (especially John). Reading and studying the New Testament exclusively will do you no favors as a student or a scholar because the New Testament is not a naturally self-contained example of Koine Greek grammar. There is no such thing as ‘New Testament Greek’ or a ‘New Testament corpus’ which should be isolated from, say, the writings of Josephus. Furthermore, the data the New Testament yields for Koine is a microscopic example of a language. When compared to the size of the corpora used in Corpus Linguistics, the entire New Testament is a single period at the end of a sentence. It contains approximately 138,000 words with 5,000 tokens. This may sound colossal to a new student, but the iWeb corpus for English has 14 billion words with tens of thousands of tokens taken from millions of webpages. It is methodologically unsound to limit study of Koine to the New Testament (another important reason we need linguists in our faculties—more on this to come).

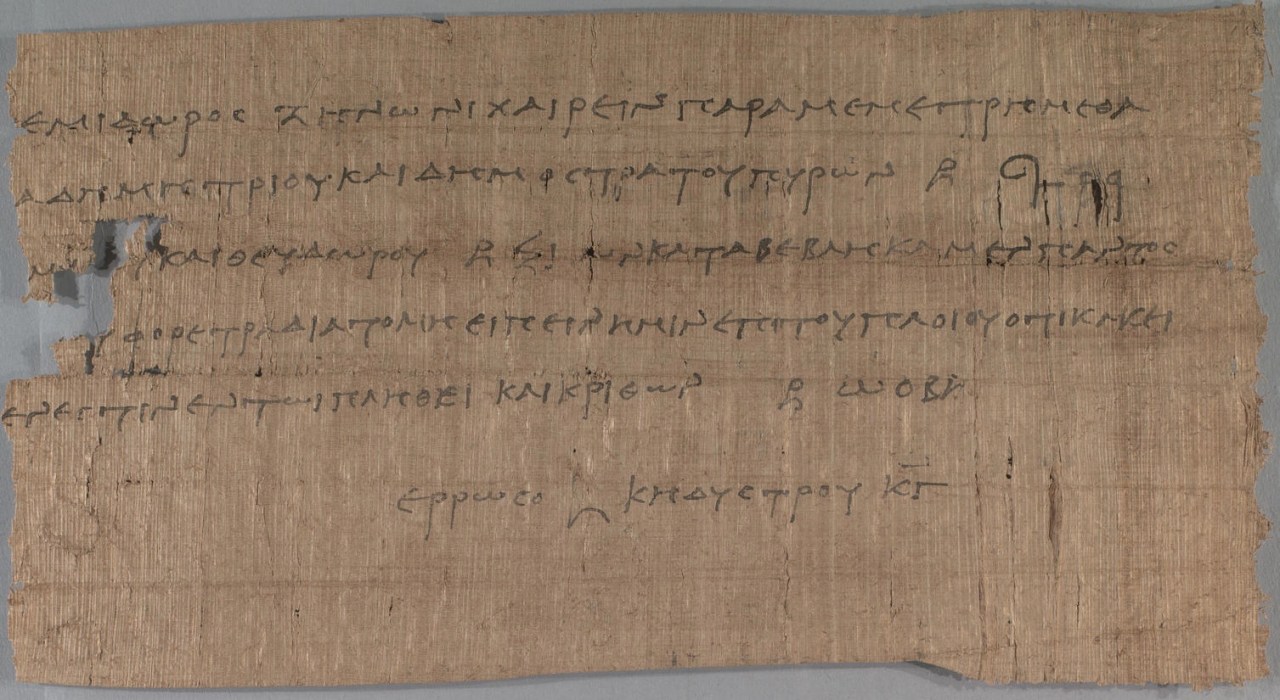

With this in mind, it is time for those who teach and study Koine to begin exploring evidence from non-biblical papyri more deeply and to begin incorporating it more clearly into their work. As Deismann wrote a century ago: this work is “of the very greatest importance.” The good news is that this evidence is not difficult to find. Thanks to the help of a generous friend (ehem, Will Ross), I’ve been working slowly through the papyri in Pestman’s reader (which is excellent by the way) and comparing them with selections from the Septuagint. It has been a humbling experience, to say the least. It has also been rewarding in a way I never expected. Yes, the data is invaluable (have you ever seen a semelfactive in the wild?). Students of Koine certainly need to explore and use it more often. But what I’ve found surprising is how moving it is to have contact with the ancients behind these documents. Translating legal transactions notarized two millennia ago, and reading the descriptions of the faces and homes described there reminds me how deeply human these people were—as human as I am today. They were so human, in fact, that they might have spent a Tuesday afternoon transacting business with a young Jew from Galilee and not thought twice about him.

Life is incredibly brief and most of us, given enough time, will be lost to the memory of human history unless some accident, like a chance papyrus protected by the Egyptian desert, preserves our memory. These people—Paniskos, Panevkounios, Nikias—were as truly alive as we are today. They had real dreams, real hopes, real fears and needs. They laughed until they cried with their friends, drank beer on warm summer evenings, and lay awake at night worried about paying bills. They had preferences, tastes, bad habits. Some were kind. Some were mischievous. And others wanted justice.

Go read these papyri to grow as a student of Koine. Absolutely. But read also to discover what is lost when we dispose with ‘dead’ languages, which appear meaningless to our current system of capital. We lose access to the literature—the legal documents, even—that reveal to us the drama of a humanity shared across vast epochs of human history.