“As Modern Greek affords us the means of enriching our understanding of Hellenistic speech, we shall not be surprised to find it help us in understanding and interpreting Hellenistic texts.”1

In a previous post, I argued that Modern Hebrew is valuable to students of Biblical Hebrew. I intend now to do the same with Standard Modern Greek (MG).

The Greek language is remarkable: not only did it outlive the Macedonian, Alexandrian, Roman, and Ottoman Empires (Ελευθερία ή θάνατος!), God himself spoke it. It is also not dead. Millions of people speak the same language as printed in your New Testament––one of the longest continuously documented languages in the world, and a remarkably stable one at that (the preposition ἀπό has been on the lips of Greek speakers for at least 2500 years). I have seen a native Greek without any training make sense of a random passage from Septuagint Numbers. That a Greek could make any sense of this text is incredible: it was produced in the 3rd BCE.

Diachrony is valuable because it provides an aerial perspective on synchronic use. MG can elucidate found data, fill gaps, and support linguistic analysis where elicitation and native speaker intuition in postclassical Greek are not available. When I was writing my thesis, I spent a summer in Athens and noticed how Greeks use a particular preposition I was researching. I would not have noticed issues with my interpretation of that preposition in PCG otherwise.

Yes, caution is warranted. We obviously cannot draw a straight line between PCG and MG. In the late 19th century, as Jews and Greek experienced an emerging national consciousness, they debated which variety would be the official ‘language’ of their nation. Greeks called it το γλωσσικό ζήτημα (The Language Controversy). One outcome of the debate for Greeks was a new language variety called Katharevousa (καθαρεύουσα). Katharevousa was built on the structure of classical Greek. It is defunct now, but its effects are permanent on Greek language and culture (e.g. the Greek constitution is written in Katharevousa). Some aspects of apparent continuity between MG and PCG are false friends, e.g. the result of Katharevousa, or other types of prescriptivism.

On that note, let’s begin with the many ways MG is different than postclassical Greek. Because there are many changes, I won’t cover them all. I am indebted to Brian Joseph for much of what follows.

Disdvantages:

(1) Phonology: There are many differences here. If you read classical or PCG, the first major change is the loss of breathing marks and most accents: by decree of a socialist Greek parliament (let the reader understand), only the tonos (acute) is written. Another major change is vowels. At some point nearly all of them conspired to become /i/ (-ει, -η, -οι, -υ). Other vowels changed in unexpected ways: the -υ in -αυ and -ευ is pronounced /v/ or /f/ based on the voicing of the letter that follows it, the diphthong -αι is /e/, and some phonemes like -ια /ja/ (e.g. σπίτια) are brand new. The letter β is also a voiced fricative /v/, and there are new phonemes like fricative /τζ/ borrowed from languages like Turkish (“σκάει ο τζιτζικας”: it’s so hot the cicada are popping). Phonetic changes also produce changes to morphology that will affect your ability to recognize vocabulary you know from PCG: εντρέπομαι > εντρέπομε > ντρέπομε > τρέπομαι.

(2) Morphology: The primary difference is verbal and nominal morphology. MG is an inflectional language but in the verb phrase, synthetic structures have been replaced by analytic ones (e.g. adjectival degree, indirect object marking, the infinitive, etc.). Word formation can be quite different. An augment is obligatory now only if the verb begins with a consonant and its stem and ending are monosyllabic. The optative is gone. The dative is gone, replaced by the Genitive (a process that began in PCG). The synthetic future has been replaced by the morpheme θα (θέλω ἵνα > θέλω να > θε να> θα). The particle να forms the subjunctive ( ἵνα > να), the morpheme αν is the conditional. Medio-passive allomorphy (-ομαι / -θη) from PCG is now the case everywhere, but the paradigms have changed dramatically.

In sum, if a Greek person asked you: Από που είσαι? And then said, Ήμουν πρόσφατα στην Αμερική! It’s familiar but cannot be understood without knowledge of the changes. You will need to learn many of the paradigms as if they were a new language.

(3) Vocabulary: Greek has many new words, including indefinite articles (ένας, μια), and other words are no longer used (you want a bottle of νερό, not ὕδωρ). Many words from AG also have a different meaning (don’t think αγαθός is a complement…).

(4) Syntax: This is a major area of discontinuity. A short survey: there’s no infinitive (except in the Pontic dialect Romeyka!) and finite complementation is now the rule (control structures are different), there are indirect genitives, probably serial verbs, clitic doubling, the position of negative polarity items has changed, the case system has been restructured, negative concord is more strict in Modern than AG, and while insubordination is known from AG, the use of insubordination for commands (να πάμε, let’s go!) is novel. Much more work is needed in this area, but you should assume change as a rule.

(5) Pragmatics: Although systems of inference arise from universals of human behavior, a convention in MG does not automatically apply to PCG. If it does, it may be the result of human behavior with language, and not the Greek language itself. To prove that an utterance of MG is functionally the same as PCG will require more than simple comparison. You cannot look at the Greek New Testament and say, “Hey! Greeks say this and mean [x]!” You’re probably right, but it needs to be carefully demonstrated across nearly 2000 years of evidence. Moreover, idioms like πιάσ’ τ’ αβγό και κούρευ’ το (catch the egg and shave it) or Η αυτοψία θα δείξει (the autopsy will reveal it) simply have nothing to do with any previous period of Greek. The same can be true of lexical pragmatics and issues of register.

(6) Verbal system: As noted above, the perfect is formed using εχω as an auxiliary, there is an imperfective future now, the infinitive has disappeared and all its functions replaced by finite clauses, and the use of participles has diminished considerably. Just two participle forms are left: imperfective active and medio-passive. In the mood system, the optative has disappeared. Other semantic features, like causation, are encoded using periphrastic constructions. There has been huge change to the verbal system and some appearances are deceiving. Learning these changes is basically like learning a new verbal system.

You might be thinking, then what is the point of learning MG?

finds your lack of faith disturbing

Let’s look at the advantages.

Advantages:

(1) Phonology. Believe it or not, MG phonology is basically in place in early Byzantine Greek (324 CE –), with many changes having begun in varieties of PCGs in the Roman period. As Brian Joseph writes, “the Classical Attic phonological system began to undergo several changes in the post-Classical period which ultimately characterize the differences between Ancient and Modern Greek.” In fact, as my friend Ben Kantor (2023) shows, MG phonology is different from some varieties of PCG in only a few main areas. The consonants are mostly the same and many vowel changes typical of MG have their origin in PCG. MG is still a stress-based system, and stress is still restricted to one of three last syllables in a word. Despite changes to clausal position, knowledge of MG will also allow you to internalize some aspects of cliticization from PCG.

It is true that MG does not preserve certain phonemic oppositions from PCG. Some might complain on this basis that it is not historical to use MG phonology to teach or read PCG texts. This is what the industry calls fake news. Greeks have always read and taught Greek texts, ancient or otherwise, the way they spoke Greek at the time. And as you can see above, MG phonology applied to PCG texts will run into fewer issues than you’d expect. In my experience, teaching communicative PCG using MG phonology has only meant I needed to write more at the beginning (and reading text is the point of learning PCG anyways). If you want to use a reconstructed phonology, fine. See Ben Kantor. But MG gets far too much flak in this area.

(2) Morphology: Yes, despite all the changes, there’s continuity here too. With exception to the dative and a few changes, the case system is basically the same in its form (MG is a fusional-inflectional language). MG even has a vocative (κλητική) still. Morphological case on the article is fairly consistent (ο / οι, τον / τους, του / των, το / τα, etc.). Preverbs are still productive. Other aspects of morphology will be familiar: the active singular (θέλω, θέλεις / θέλετε, θέλει / θέλουν), the perfective aspect marker -σ (θέλησα), the use of the augment in past tense progressive (ήθελα), and an opposition between realis and irrealis negation is still in place. Other aspects of MG hearken back to the productivity of the same morpheme in PCG, like the comparative -τερος in καλύτερο and μαγαλύτερο. Some verbs from Ancient Greek will be easily recognized (Βλέπει / είδε), while the difference for others is easily learned (λέγει > λεει).

If you imagine it’s the year 1400, and you’re looking at a map of Europe 600 years in the future, that is basically what MG morphology is like: same topology, some familiar names and features, but much would be new and require explanation. Once explained, it makes perfect sense.

(3) Vocabulary: This is the area where I think knowledge of MG is most beneficial. In a vast amount of cases, a word from MG is basically an AG word whose morphology is different. By learning MG, you are inadvertently learning huge amounts of the PCG lexicon. I don’t know how many times I have been looking at a PCG text, like a papyrus, and some random lexeme is basically identical in MG. Yes, some common words were resurrected by Katharevousa (e.g. μέχρι), but many others are the same because the lexicon is very stable (e.g. cardinal and ordinal numbers, εγω, καθαρό, καλό, θέλω, πόσο, θάλασσα, αναχωρώ, μεγάλο, κτλ.). And with knowledge of small phonetic changes, you can recognize vast amounts more (ποτήριον > ποτήρι, ἡμέρα > μέρα, etc.). There are also many words you might not take the time to learn in PCG that you learn automatically in MG (cucumber, ἄγγουριον > αγγούρι). Even the word hi (γεια) has a simple foundation in ancient Greek (υγεία σοῦ > γεια σου > γεια).

(4) Syntax: There is obviously a lot of difference here. But certain elements like wh-words, the relative clause, island-effects, filler-gap dependencies (fillers enter into Greek during PCG), and sluicing appear very similar to PCG (more research is needed in this area). The order of constituents in the noun phrase is identical to MG, and modifiers require concord in case, number, and gender. MG is still a pro-drop language. Depending on the analysis, PCG and MG each have satellite-framing tendencies (directional satellites are common but there’s still issues of classification). The article can be used to nominalize clauses in MG (a common function from PCG). Other aspects of syntax, like left dislocation (or clitic doubling) and topicalization can be recreated almost exactly from PCG, with the same functions. This is not to mention all of the banal continuity between AG and MG (e.g. the definite article, possessive genitive, present progressive).

(5) Verbal system. Much has changed, much has stayed the same. As Brian Joseph writes, “the categories and forms of the verbal system of Ancient Greek are generally valid for the Koine, though with some changes, and even, to some extent for Medieval and Modern Greek as well.” Aspectual oppositions are the same (perfective, imperfective, perfect), and with exception to a few changes, valency patterns can be close if not identical to their PCG counterpart. Certain alternations also have clear continuity with their PCG counterparts, and voice semantics can be remarkably similar. Like PCG, MG allows null objects, often under the same conditions as PCG.

(6) Discourse. Another huge area of benefit. You will recognize certain particles from PCG (αλλά, επειδή, διότι, etc.). Other conjunctions from AG are still in use (όμως, ώστε, etc.). The about-topic marker για patterns like its ancient counterpart περί. Greek is still a topic-prominent language, meaning discursive strategies for topic-continuity are functionally the same. The left-periphery is identical to PCG, and while the dominant word order is probably SV, VS is also common. Like PCG, grammatical relations do not determine WO. The demonstrative article is easily learned (αυτός, αυτή, αυτό), and used for the same discourse functions as PCG. To speak MG, you need to know how to generate Greek discourse, including strategies for stance taking and turn taking, as well as encoding minor and major transitions in structure, performing speech acts, introducing and focalizing referents, directing attention, and more. Despite some differences in code, much of this is shared in common with PCG.

(7) Diachrony: The primary benefit of learning MG is an aerial view of the history and evolution of the language. You cannot be better prepared for research if you are equipped with this knowledge. Knowledge of MG “serves to establish forms for which there is no certain textual tradition.” As I have noted above, other aspects are useful: the development of the verbal system and verbal syntax, the continuity of the nominal domain, negative concord, constituent order and information structure, lexical semantics, and more.

(6) Pragmatics. Without knowledge of MG, it might be difficult to understand the use of ταῦτα (ὅδε in Classical) for emotional deixis. In MG one might say: ‘Here are my thoughts and feelings about this topic. αυτό.’ What they mean is: ‘That’s all I have to say about that’. Likewise, scholars have argued the perfect in PCG can be used to communicate that a state of affairs is relevant at the current speech time. Despite differences in morphology, knowledge of the MG perfect (see Holton et al. 2004) makes such an analysis completely unsurprising. And because of the interaction of grammar and logic, one cannot use ή (or) except in the very same way it is used in AG: to code disjunction (either inclusive or exclusive).

Love it or hate it, Greeks have been on about this type of stuff for years, and not without cause.

If anything, knowledge of MG would allow scholars to save quite a lot of time, not treating as theory in PCG what is a well-known fact in MG (and vice versa: arguing a theory for PCG that has no coverage in the diachrony of Greek). Obviously not everything in MG is helpful (pace Caragounis), but I suspect in the years to come we will discover that MG was more useful for studying PCG than scholars originally thought possible.

Conclusion

Should you learn MG? Yes. Learning MG is at least an exercise in statistical learning. Where it shares features with PCG, you are internalizing those features and developing intuitions about the language as a system. Greek is not dead. It organically shares many features of PCG, including large parts of the grammar and lexicon, phonology, aspects of morphosyntax, and more. By learning to speak MG, you are inadvertently learning those aspects of PCG as well. Do you need MG to learn PCG? No. Obviously not. Use Biblingo for that. The point I set out to make here should be clear: knowledge of MG is useful for learning and essential to research. If you work on historical periods of Greek without knowledge of MG (even if you’re simply a biblical scholar), certain questions will be needlessly troublesome, and your research could be negatively impacted.

To those who think I am nuts, remember that many of the philologists of yore (Moulton, Robertson, etc.) believed exactly the same thing I have argued here. In fact, as this blog’s overlord once suggested, knowledge of MG is probably a higher priority for researching texts like the Greek NT than German.

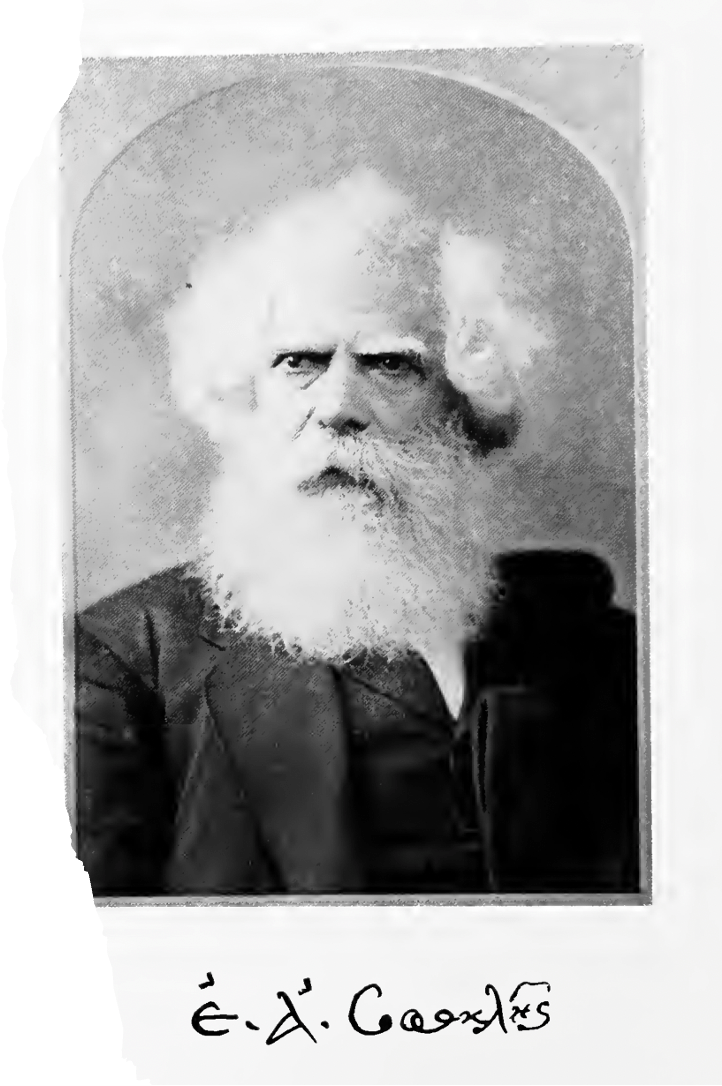

- Albert Thumb, “On the Value of Modern Greek for the Study of Ancient Greek”, The Classical Quarterly Vol. 8.3 (Cambridge University Press, 1914), 191. ↩︎