As Rachel and Michael Aubrey finish up the revisions for the print edition of Greek prepositions in the New Testament, we want to give some reflections on our motivations for writing this book—a version of this will appear in our expanded introduction to the book.

When we research, write, and present on the topic of prepositions, one of the major issues that stays at the front of our mind is how our work relates to existing tools. Particularly, we want to balance out ways in which traditional grammars and dictionaries present information about these small, but important words. Prepositions are relational words that orient one person, object or item relative to another: The apple is in the basket. The English preposition in points the reader to the relative position of the apple: inside the basket.

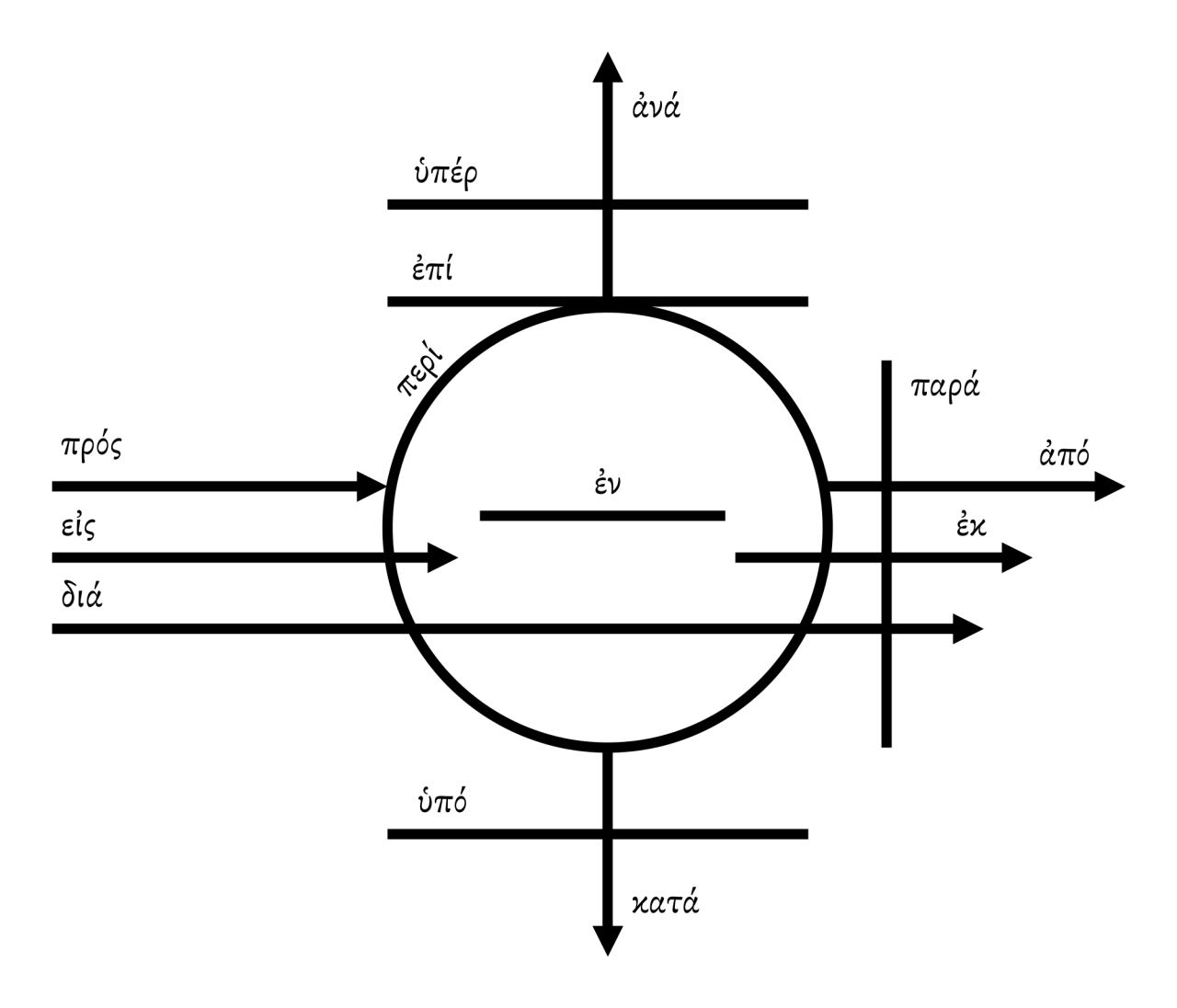

In standard grammars, both for teaching and reference, there are two common strategies for presenting prepositions: charts of spatial usage and lists of glosses. Readers may recognize some version of the chart below, here adapted from Dana and Mantey’s (1927, 113) Manual Grammar of the Greek New Testament. Their chart is a common source for similar charts in various other publications, including Mounce (2019, 419) and Wallace (1996, 358), who each supplement some basic information about what cases are required. A common type of visual representation for prepositions is in Figure 1 below:

Figure #1: A common type of visual representation for prepositions

The trouble is that these types of visual figures only communicate spatial meaning, and only a single spatial meaning for each preposition. As a result, such spatial figures fail to provide guidance for Greek students when they encounter abstract uses of prepositions or how spatial and abstract uses are related to each other. Additionally, spatial charts such as in Figure 1 usually only provide information about the so-called “proper” prepositions in such charts.*

* The distinction between “proper” and “improper” prepositions is defined only by whether a preposition is also used to attach as a prefix on a verb. This has nothing to do with the actual criteria of “properness” for any of these words as prepositions.

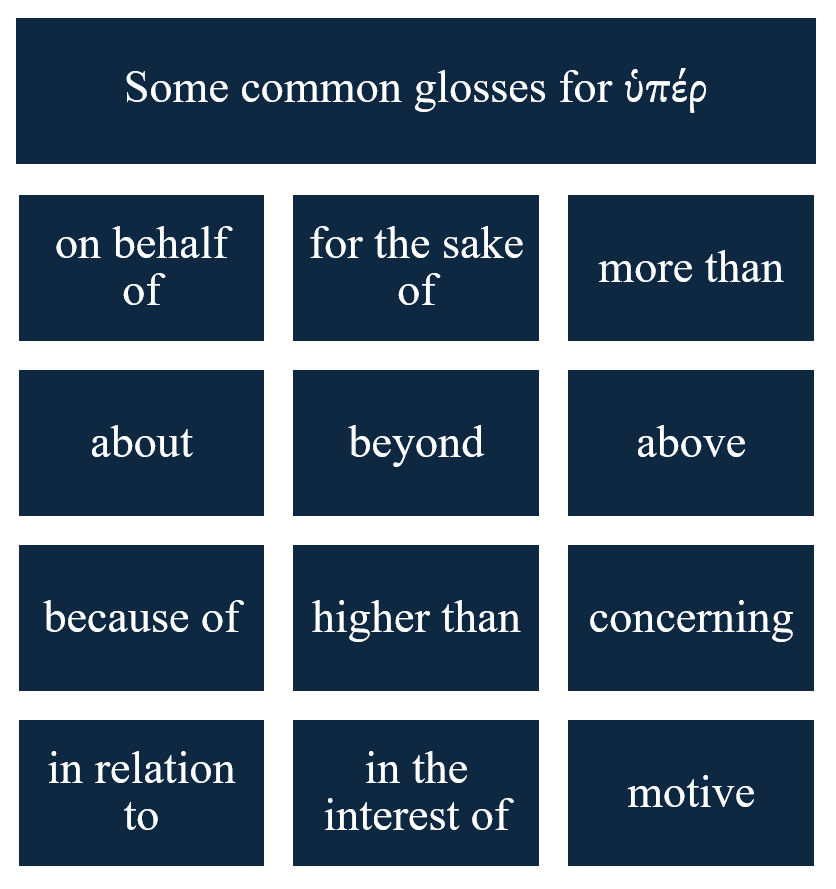

Beyond these spatial charts, it is common for grammars to rely on lists of prepositions and senses, which is also the default strategy of presentation for dictionaries. This has its own consequences for how students learn about and engage with prepositions. Lists in grammars vary in how much information they provide from fairly sparse to several dozen pages, depending how many examples they provide. Some are quite short (e.g. Whitacre 2021: 355–359) and others are longer (e.g. Wallace 1996, 355–389; Porter 1999, 139–180). But all generally rely on glosses for translation rather than elements of meaning internal to Greek grammar. The challenges that arise from this approach are equally true of both grammars and dictionaries, but because the latter tend to be more comprehensive, let us focus on dictionaries. A dictionary entry for a preposition might be quite comprehensive for the corpus that it is designed for, but it often still obscures the relationships between the different senses of a preposition.

Consider BDAG’s entry for the preposition ὑπέρ, ‘over’.* One notable point in the entry for this preposition is the editors’ assertion at the beginning: “The locative sense ‘over, above’ is not found in our lit. (not in the LXX either, but in JosAs 14:4; ApcEsdr 1:9; Just., Tat., Ath.) but does appear in nonliteral senses” (BDAG, 1030). This assertion obscures how common spatial ὑπέρ is. Not only is the provided list too short (with no mention of Philo, Josephus, and other contemporary authors), but it is also inaccurate with regard to the usage of ὑπέρ, ‘over’ in the Septuagint. There are multiple locative uses of this preposition in the LXX, such as those in Examples 1–2.

* This discussion builds on Rachel Aubrey (2022).

καὶ προσέταξεν Κύριος ὁ θεὸς κολοκύνθῃ, καὶ ἀνέβη [ὑπὲρ κεφαλῆς τοῦ Ἰωνᾶ] τοῦ εἶναι σκιὰν ὑπεράνω τῆς κεφαλῆς αὐτοῦ, τοῦ σκιάζειν αὐτῷ ἀπὸ τῶν κακῶν αὐτοῦ·

And the Lord God commanded a gourd, and [its leaves] rose up [over the head of Jonah] to provide shade over his head to shade him from his bad things. (LXX Jonah 4:6)

καὶ ἀπέστειλας πρέσβεις [ὑπὲρ τὰ ὅριά σου], καὶ ἐταπεινώθης ἕως ᾅδου.

and you have sent elders [over = beyond your borders] and were brought down to Hades (LXX Isaiah 57:9)

Both of these examples illustrate how spatial meaning is realized with the preposition ὑπέρ, ‘over’ in the genitive and accusative cases, respectively. The first describes a scene involving the leaves of the gourd rising up and over Jonah. The gourd leaves and Jonah are presented as having a spatial relationship relative to each other: leaves over Jonah. The second presents a scene where Jewish elders travel over the borders of one nation into another. The elders and the national boundary have a spatial relationship: the elders over the border. Awareness and understanding of contemporary examples like these become highly relevant for how we describe this preposition. But since they play no role in lexical analysis, they leave dictionary users unprepared to understand the entry.

In BDAG, lexicographers excluded these spatial senses because they do not appear in their corpus (the New Testament and other early Christian literature). As a result, the organization of the entry effectively becomes arbitrary. The spatial meanings of ὑπέρ, ‘over’ provide grounding and motivation for how nonspatial meaning arises. Without them, the editors lose their ability to provide any kind of explanation for where the preposition’s nonspatial meaning comes from. The resulting BDAG entry becomes little more than a list of inadequately organized translation glosses. Various senses end up seeming incidental as though they are not connected in any intrinsic manner.

BDAG’s entry lists several senses, in order, that we can label as: beneficiary, cause/reason, topic/content, and degree beyond.* Each of these is motivated by basic spatial scenes. For instance, spatial location above blends with beneficiary in protective or defensive scenes. We can illustrate a progression from purely spatial expressions to purely benefactive expressions in the four sentences in Example 3.

* BDAG also includes a brief discussion of an adverbial use of ὑπέρ, ‘even more’, which is an extension of their degree beyond sense.

- Spatial Configuration

καὶ τὸ [ὑπὲρ Ἱεριχοῦντος] φρούριον ὀχυρότητι

[Above Jericho] he built the walls of a fortress (Josephus, Wars 1.417).

> Spatial Configuration motivates Benefactive Protection

καὶ ὑπερασπιῶ [ὑπὲρ τῆς πόλεως ταύτης]

I will be a shield [over this city] (LXX 4 Kingdoms 19:34).

> Defensive Action is construed as Benefactive Protection

καὶ Κύριος ὁ θεὸς πολεμήσει [ὑπὲρ σοῦ]

And the Lord God will do battle [for you] (LXX Sirach 4:28).

> Benefactive Configuration

διὸ αἰτοῦμαι μὴ ἐγκακεῖν ἐν ταῖς θλίψεσίν μου [ὑπὲρ ὑμῶν], ἥτις ἐστὶν δόξα ὑμῶν

Therefore I ask you not to be discouraged at my afflictions [over/on behalf of you], which are your glory (Eph 3:13).

Just as walls stand above the people of a city, the Lord can place himself over others to protect them or do battle in a way that protects them. Protective and defensive contexts like this provide motivation for semantic extensions from “walls over Jerusalem” to “my afflictions over you.”

Patterns such as this are readily found for all of the figurative senses of ὑπέρ, ‘over’, and seeing them beside each other helps students and language learners better understand how prepositional meaning is built out as a family of senses based on usage. Because of the lack of explicit spatial senses in the New Testament, one might imagine that ὑπέρ, ‘over’ is unique in its problems as a dictionary entry. However, the larger picture is more or less the same for all prepositions. Across the board, dictionaries make little effort to link spatial senses to figurative ones. This is because dictionaries are designed to provide an enormous amount of lexical information in compressed spaces. As a result, lexicographers are forced to make difficult choices in terms of what information is presented and its order. Because the dictionary tradition, generally, presents senses as a list, those senses also seem entirely discrete and separated from each other.

Further, because the glosses that dictionaries provide are translation glosses, target language conventions (for BDAG, English), place limits on the dictionary user’s ability to draw relationships between glosses: “for”, “beyond’, “above”, and “concerning” share little resemblance between each when represented in English. This is because the conventions of preposition usage, both for spatial and figurative meanings, are highly language specific. When these differences are necessarily in a bilingual dictionary, users will struggle to understand the relationships between the senses expressed by those glosses.

Here is a closing thought: Neither traditional grammars nor dictionaries are inherently bad. They are, in fact, quite good. People use them every day. They are and will continue to be highly useful. If you work in Biblical or Postclassical Greek, you should have access to a copy of BDAG on your shelf, in your digital library, or at your school. If you do not yet have a copy and would like to get one, here’s the link: BDAG on Amazon. You should also get access to at least one reference grammar: two recent ones include Whitacre (2021) and von Siebenthal (2019).

We only call attention to how these more traditional reference works have built-in choices for structure and tradition and that, in turn, those built-in choices have implications for how students approach prepositions. In our ongoing work on Greek prepositions, our purpose is not to disparage, but to provide a supplementary set of tools to help students learn and engage with prepositions—and hopefully in the long-term a comprehensive and linguistically-grounded reference grammar. We want readers to have a full picture of how our work on prepositions relates to standard teaching and reference works that are more familiar.

Works cited

Arndt, William, Frederick W. Danker, Walter Bauer, and F. Wilbur Gingrich. 2000. A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Aubrey, Rachel. 2022. “Exploring perspective in preposition analysis.” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature, Denver.

Aubrey, Rachel & Michael Aubrey. 2020. Greek prepositions in the New Testament: A cognitive-functional description. Digital Edition. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press.

Aubrey, Rachel & Michael Aubrey. 2025. Greek prepositions in the New Testament: A cognitive-functional description. Second Edition. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press.

Dana, H.E. & Julius R. Mantey. 1927. A Manual Grammar of the Greek New Testament. New York: Macmillan.

Mounce, William D. 2019. Basics of Biblical Greek grammar. 4th Ed. Grand Rapids: Zondervan.

Porter, Stanley E. 1999. Idioms of the Greek New Testament. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press.

Wallace, Daniel B. 1996. Greek Grammar Beyond the Basics: An Exegetical Syntax of the New Testament. Grand Rapids: Zondervan.

Whitacre, Rodney A. 2021. A Grammar of New Testament Greek. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.