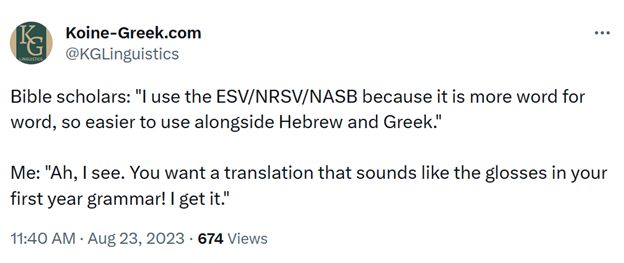

Formal translations are defined by a set of conventional word and construction pairings between the source languages (Greek & Hebrew) and the receptor language (in this case, English). Where did those pairing come from? How were they chosen?

I think it’s important that we understand what I mean when I write something like this.

First of all: I genuinely and wholly-heartedly believe that everyone should read a translation that speaks to them. And if a formal translation, like the ESV or NRSV does that for you, that is a good and excellent thing. Read that Bible.

Formal translations are not bad. And they serve important functions. If you want a Bible to sit and have open beside your Greek or Hebrew text that evinces a structural consistency parallel to the Greek or Hebrew, there is certainly value in having that.

Functional translations are also not bad. If you want a Bible to sit and have open beside your Greek or Hebrew text that emphasize the naturalness of English in a way that respects the naturalness of the original Greek or Hebrew, then there is also value in having that.

(English celebrates a multiplicity of high quality translations so vast that it is shameful how just how many minority languages with worshiping Christian churches struggle to read a Bible in a second, third, or fourth language.)

In English, when we talk about word-for-word translations, what are we actually talking about? Where does “literal” translation come from? What makes a translation word-for-word? Because these are not concepts that exist “out there” with their own ontological status. There is no platonic form of literalness. Rather, literalness arises from a historical traditional of glossing grounded in a historical tradition of grammar description and instruction. Formal translations are defined by a set of conventional word and construction pairings between the source languages (Greek & Hebrew) and the receptor language (in this case, English).

Your first year and second year Greek and Hebrew grammars, as well as your vocabulary glossaries, gave you a specific map for connecting the forms in the source languages to the forms of English (or Spanish!). Formal translations look they way to do because the grammars and dictionaries specify specific glosses for specific words and constructions. In turn, when biblical scholars teach that grammatical tradition of word/construction pairings between source and receptor and students intuitively come to associate those pairs with transparency to the Greek or Hebrew. It is the chicken-egg problem. A formal translation is “word-for-word”—is literal—for that reason: ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny. These are emergent conventions that exist right under our noses. But they are still just that: conventional. If the map in your grammar was different—and it easily could have been—what constitutes “literal” would look entirely different to you.

We can and should interrogate these concepts and grow from them. We should challenge the people writing our introductory grammars to think about better or more modern glosses to words or phrases they teach. We don’t need to teach students that λύω mean ‘I loose’. We can evaluate what it means for something to be word-for-word and what it means to be sense-for-sense or any of these terms that often cause misunderstanding in the prefaces of the new English translations.

And we can continue enjoying reading all the formal and functional translations that we all already have and love. It’s perfectly fine to have and prefer a translation that sounds like the glosses in your first-year grammar. Does it communicate to you effectively? That’s what’s important.

We simply also need to ask ourselves a few questions. Are we satisfied with our grammars? Are we satisfied with our glossaries and our dictionaries? John Lee’s A History of New Testament Lexicography says we shouldn’t be for the latter and a comparable book for grammar would certainly come to the same conclusion.

It is important for us to know that the grammar our translation sounds like is what makes that word-for-word experience possible. Knowing that should be empowering to you as you read and think about the nature of the English Bible in front of you and also the nature of the grammar you learned your languages from.