This is an excerpt from the introduction to our forthcoming book on Greek prepositions.

When we talk about the semantics of prepositional phrases, we are talking about a specific kind of conventionalized pattern. Conventional patterns are arbitrary in the sense that they are not predictable from one language to another. But in another way, they are nevertheless motivated (Sweetser 1990). There is a reason they occur as they do. Basic cognitive processes influence how different prepositions extend from spatial meanings to more abstract ones.

The preposition on is commonly associated with fire and ignition in English because of the necessary orientation of a flame under what it consumes. The verb set expresses both a spatial and motion relationship with one object placed on another object. The act of placing an object on an existing fire is extended metaphorically to the ignition of a fire: set a log on the fire → set the log on fire.

The spatial relationship between a log (TRAJECTOR) and fire (LANDMARK) is construed as vertical contact (set a log on the fire), which then motivated a metaphorical extension for ignition of a log (set the log on fire). This kind of metaphorical mapping relies on the iconic relationship between the formal expressions and the spatial relationships between logs, fire, and ignition. Lakoff and Turner (1989, 157) describe iconicity as a type of metaphorical structure where the structure of language shows correspondence with the structure of its meaning. This is a way of expressing this meaning (ignition of a fire) that is specific to English and does not occur in Ancient Greek. Another example of abstract usage with the preposition on may be illustrated by the sentences in example (1).

- My phone died [on me] and I didn’t have a charger.

My car died [on me] and I’m stuck in the parking lot without jumper cables.

My blender died [on me] and I can’t finish making my smoothie.

English speakers know such sentences are not about the spatial orientation of someone’s phone on top of them. This preposition expression functions within a larger frame: something I rely on has failed in some way and it did so in a manner that is highly inconvenient or burdensome. It developed as an English expression through a family of conceptual metaphors and embodied experience. Burdens weigh us down. They involve vertical orientation and weight from force of gravity pushing down upon us* English loves this conceptual structure for the preposition on. Various sentences illustrate this in example (2).

* For children, patterns like this are learned by themselves and then integrated into the network of sense of the prepositions (Tomasello 2003, 57).

- This situation has been difficult [on my father].

I wouldn’t wish my situation [on my enemy].

I’m sorry I blew up. There’s a lot of pressure [on me] right now.

I hate to impose [on you] in this way.

There is an expectation [on you] to make the right decision.

If we were writing a description of English prepositions, we might call these kinds of English prepositional phrases burden expressions for the preposition on.** Often, native English speakers use abstract expressions of on without awareness of its extension from the spatial domain to the abstract: it just means on. What else would it mean?

** For a fuller treatment of this English preposition, see Lindstromberg (2010, 51–71).

This is an important point to understand because as we illustrated above it is not uncommon—especially in the grammar-translation tradition—to treat Greek prepositions as discrete sets of meaning primarily based on various English glosses used for translating them. But Greek speakers, if you collected a variety of instances the preposition ἐπί, would say basically the same thing: they all just mean ἐπί.

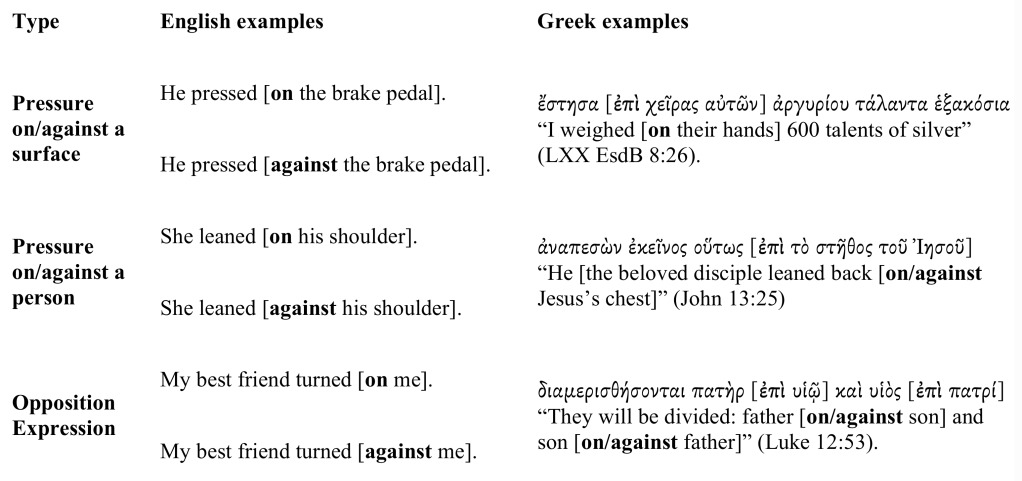

The types of usage expressed by the Greek preposition ἐπί, ‘on’, rely on similar patterns. Below we can trace how English on and Greek ἐπί both extend from one object exerting downward force on another to two people in conflict with each other. On the English side, we also highlight how English “on” overlaps with “against”. Both require the exertion of force.

| Type | English Example | Greek Example |

| Pressure on/against a surface | He pressed [on the brake pedal]. He pressed [against the brake pedal]. | ἔστησα [ἐπὶ χεῖρας αὐτῶν] ἀργυρίου τάλαντα ἑξακόσια “I weighed [on their hands] 600 talents of silver” (LXX EsdB 8:26). |

| Pressure on/against a person | She leaned [on his shoulder]. She leaned [against his shoulder]. | ἀναπεσὼν ἐκεῖνος οὕτως [ἐπὶ τὸ στῆθος τοῦ Ἰησοῦ] “He [the beloved disciple leaned back [on/against Jesus’s chest]” (John 13:25) |

| Opposition Expression | My best friend turned [on me]. My best friend turned [against me]. | διαμερισθήσονται πατὴρ [ἐπὶ υἱῷ] καὶ υἱὸς [ἐπὶ πατρί] “They will be divided: father [on/against son] and son [on/against father]” (Luke 12:53). |

We see an appreciative amount of overlap in these examples between English “on” and Greek ἐπί. In these examples, we can trace the progression of downward force in a basic spatial scene (the force of one object on another object) to an abstract scene of conflict that involves opposition between two parties: two opposed forces pressing against each other. The final result, opposition expressions, involve the blending or merging of the spatial scene (the source of the preposition usage) with an entirely different domain of usage: scenes of conflict. These blended scenes then become conventionalized aspects of preposition usage for the language. In this way, prepositions are space builders (Coulson 2006, 22–23), they help language users build out the geography (whether physical or abstract) of a scene and organize the relationships between people, things, ideas, and concepts.

It is helpful for readers, when they encounter a preposition usage that seems unexpected, to pause to consider the scene in which it exists and compare it to its more basic spatial usage. As a brief exercise, consider the following English and Greek examples. How might you explain the English in terms of the larger collection of burden expressions above? Likewise, how might you explain the Greek example in terms of downward force and opposition expressions in examples (3–4)?

- The next round is on me (= “I will pay for the next round of drinks)

- οἱ δὲ ἐκτιναξάμενοι τὸν κονιορτὸν τῶν ποδῶν [ἐπ’ αὐτοὺς] ἦλθον εἰς Ἰκόνιον

So after shaking off the dust from their feet [against them], they went to Iconium (Acts 13:51).

Not all English burden expressions necessarily map directly to Greek ἐπί. Nor do all Greek opposition expression map directly to English on. This should not surprise anyone: different languages communicate in all sorts of different ways.

Preposition constructions, both spatial and abstract, are conventional pairings of form and meaning, so even when there are broadly similar correspondences in spatial usage, there will always be specific uses that are unpredictable. When that happens, it is essential to shift our mindset from seeking out predictability and pursue understanding motivation instead.

The most important point is that different meanings of a preposition are motivated by the company they keep. If a writer changes the object of the preposition (the LANDMARK) or changes the TRAJECTOR it has a relationship with, that person changes the nature of the relationship between them. The preposition is the grammatical marker of that relationship.

Works cited

Coulson, Seana. 2006. Semantic leaps: Frame-shifting and conceptual blending in meaning construction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lakoff, George and Mark Turner. 1989. More than cool reason: A field guide to poetic metaphor. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lindstromberg, Seth. 2010. English Prepositions Explained. Revised Edition. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Sweetser, Eve. 1990. From etymology to pragmatics: Metaphorical and cultural aspects of semantic structure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tomasello, Michael. 2003. Constructing a language: A usage-based theory of language acquisition. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.