In its spatial sense the preposition περί refers to the location of a TRAJECTOR around a LANDMARK. That might be clothing or jewelry, as in example (1).

- καὶ ἐξῆλθον οἱ ἑπτὰ ἄγγελοι οἱ ἔχοντες τὰς ἑπτὰ πληγὰς ἐκ τοῦ ναοῦ, ἐνδεδυμένοι λίνον καθαρὸν λαμπρὸν καὶ περιεζωσμένοι [περὶ τὰ στήθη] ζώνας χρυσᾶς

And the seven angels who had the seven plagues came out from the temple, dressed in clean, bright linen garments, and girded with golden belts [around their chests] (Rev 15:6).

Here, golden belts are the TRAJECTOR and they are are girded around the chests of the angels, the LANDMARK. Likewise, below in example (2), the leather belt (TRAJECTOR) extends in space around John the Baptist’s waist (LANDMARK).

- καὶ ἦν ὁ Ἰωάννης ἐνδεδυμένος τρίχας καμήλου καὶ ζώνην δερματίνην [περὶ τὴν ὀσφὺν αὐτοῦ]

And John was dressed in camel’s hair and a belt made of leather [around his waist] (Mark 1:6)

It can even be the motion around a landmark, as in example (3).

- Κύριε, ἄφες αὐτὴν καὶ τοῦτο τὸ ἔτος, ἕως ὅτου σκάψω [περὶ αὐτὴν] καὶ βάλω κόπρια

Sir, leave it [a fig tree] alone this year also, until I dig [around it] and put manure on it (Luke 13:8)

Here, we can trace a scanning path following the motion of servant digging (TRAJECTOR) around the fig tree (LANDMARK).

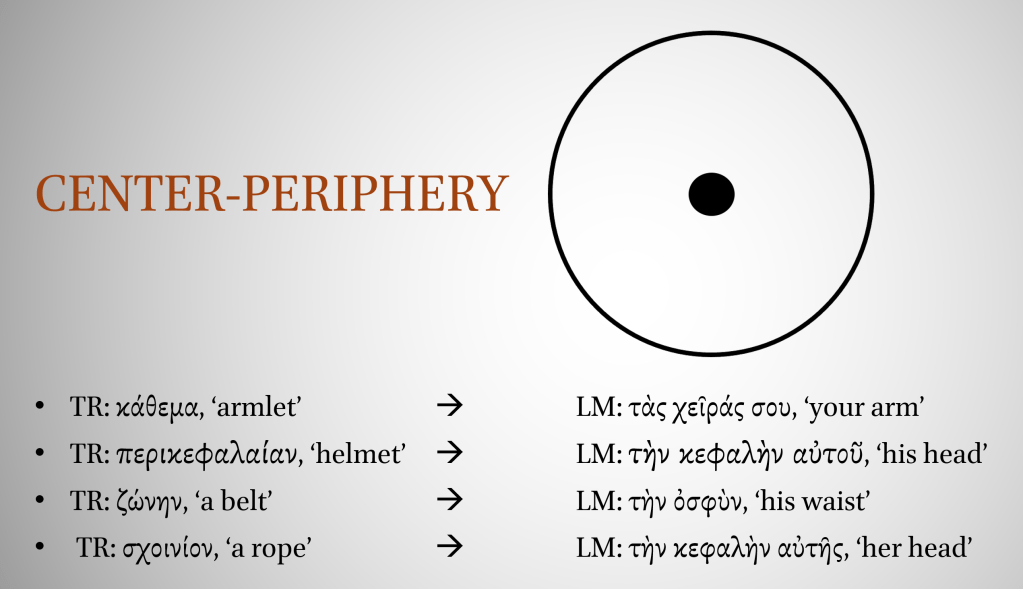

But that’s space. There are plenty of abstract uses of the preposition περί as well—the most comment is TOPIC with verbs of thought and communication. But with many other non-communication situations, the preposition περί often functions to express category structures. It’s spatial sense “Location Around” still provides motivation, but it is reconstrued metaphorically as a point in conceptual space that affects actions or circumstances in its proximity around it. This is also how we experience space: if we are the center, we have more influence over objects in our immediate vicinity than farther away and then horizon functions as a distant periphery. This is the CENTER-PERIPHERY image schema (Johnson 1987, 124-5). Radden (1989, 448) terms these AREA expressions, which he defines as, “the thematic context or field within which an event is seen. To refer to an area means to make use of a system of classification.”

Consider Sirach 37:10–11 in example (4):

- μὴ βουλεύου μετὰ τοῦ ὑποβλεπομένου σε, καὶ ἀπὸ τῶν ζηλούντων σε κρύψον βουλήν· μετὰ γυναικὸς τῆς ἀντιζήλου αὐτῆς καὶ μετὰ δειλοῦ [περὶ πολέμου] καὶ μετὰ ἐμπόρου [περὶ μεταβολίας] καὶ μετὰ ἀγοράζοντος [περὶ πράσεως], μετὰ βασκάνου [περὶ εὐχαριστίας] καὶ μετὰ ἀνελεήμονος [περὶ χρηστοηθείας], μετὰ ὀκνηροῦ [περὶ παντὸς ἔργου] καὶ μετὰ μισθίου ἀφεστίου [περὶ συντελείας], οἰκέτῃ ἀργῷ [περὶ πολλῆς ἐργασίας], μὴ ἔπεχε ἐπὶ τούτοις [περὶ πάσης συμβουλίας].

Do not plan with one who looks suspiciously at you, and hide counsel from those who are jealous of you: with a woman of her rival, and with a coward [περὶ war], and with a merchant [περὶ business], and professional salesmen [περὶ a deal], with envious people [περὶ gratitude], and with the cruel people [περὶ being good hearted], with lazy people [περὶ any work], and with a migrant labor [περὶ finishing the job], to a lazy servant [περὶ much work]— do not hold out over these [περὶ any counsel].

(Sirach 37:10–11).

Obviously Ben Sira’s attitudes toward the working and immigrants class isn’t great, so let’s focus on the preposition semantics and not the message. Ben Sira lays out a list of people to avoid when it comes to making plans or seeking advice. Each landmark establishes a category or frame and each trajector presents a person who functions within that category or frame in what the author considers an unreliable or untrustworthy manner.

| LM Category | → | TR Unreliable Participant |

| war | → | cowards |

| business | → | merchants |

| sales | → | professional salesmen |

| gratitude | → | envious people |

| good-heartedness | → | cruel people |

| work | → | lazy people |

| finishing a project | → | migrant workers |

| much work | → | lazy slaves |

In each case, the LANDMARK provides the category and the TRAJECTOR functions as a constituent part of that category. These examples are hierarchical: the LANDMARK is superordinate to the TRAJECTOR: cowards have a role within the domain of war. Merchants have a role with in the domain of business. Lazy people have a role within the domain of work and so forth.

Of course, not all instances of περί AREA expressions are so hierarchical. That’s because category structures and frames do not need to be activated with a superordinate entity to be activated. There’s a common refrain in frame semantics: Activate Part of a Frame, Activate the Whole Frame. That’s because frames are cognitive scripts when you initiate a script that everyone knows: then the speaker and hearer then can rely on shared information about that script in their communication and interaction (cf. Fillmore 2003; Fillmore & Atkins 1992). This is a concept I discussed in my short note on how definite articles work—that’s frame semantic at work.

So for περί and AREA expressions, the LANDMARK does not always need to be a higher order category. That’s what we see in example (5).

- ἀπεκρίθησαν αὐτῷ οἱ Ἰουδαῖοι· [Περὶ καλοῦ ἔργου] οὐ λιθάζομέν σε ἀλλὰ [περὶ βλασφημίας], καὶ ὅτι σὺ ἄνθρωπος ὢν ποιεῖς σεαυτὸν θεόν.

The Jews answered him, “[Περὶ good deeds], we aren’t stoning you, but [περὶ blasphemy] and because you are man though you make yourself God (John 10:33).

Here the larger scene and category is forensic—judgment. And the speakers make two assertions with these prepositional phrases. First they assert that good deeds and stoning are not part of the same script, then following the conjunction ἀλλὰ they assert what is: blasphemy. Blasphemy and stoning are part of a shared script in 1st century Jewish cultural frames. Instead of providing the higher order category, the LANDMARK and TRAJECTOR are simply two possible elements that share the same higher order category.

There’s more to abstract expressions of περί, but this is what I have been thinking about lately, as Rachel Aubrey and I finish our revisions for the 2nd (and print!) edition of Greek Prepositions in the New Testament: A Cognitive-Functional Description. We’ve revised numerous articles, written a 5,000 word introduction, expanded the glossary and added more examples.

Works cited:

Fillmore, Charles. 2005. Frame semantics. In Dirk Geerearts (ed.) Cognitive linguistics: Basic readings, 373-400. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Fillmore, Charles. & B. T. Sue Atkins 1992. Toward a frame-based lexicon: the semantics of risk and its neighbors. In Adrienne Lehrer and Eva Feder Kittay (eds.) Frames, fields and contrasts: New essays in semantic and lexical organization, 75–102. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Johnson, Mark 1987. The body in the mind: The bodily basis of meaning, imagination, and reason. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Radden, Gunter. 1989. Semantic roles. In René Dirven (ed.) A user’s grammar of English: Word, sentence,

text, interaction, 421-472. Frankfurt: Verlag Peter Lang.