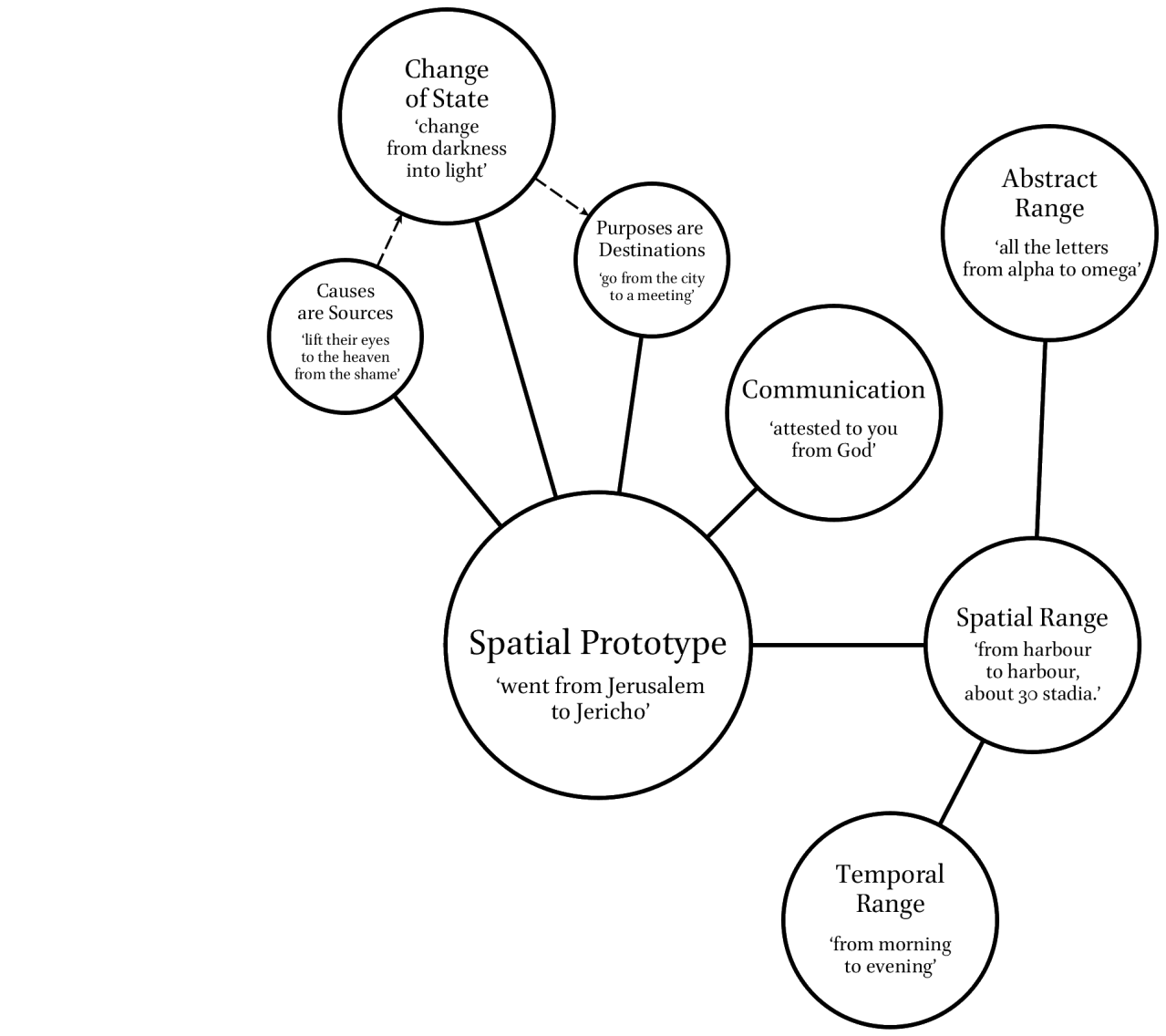

The complex network of SPG constructions, from our SBL 2023 presentation (YouTube), has a number of organizing properties. We wanted to summarize the insights of grammatical analysis here.

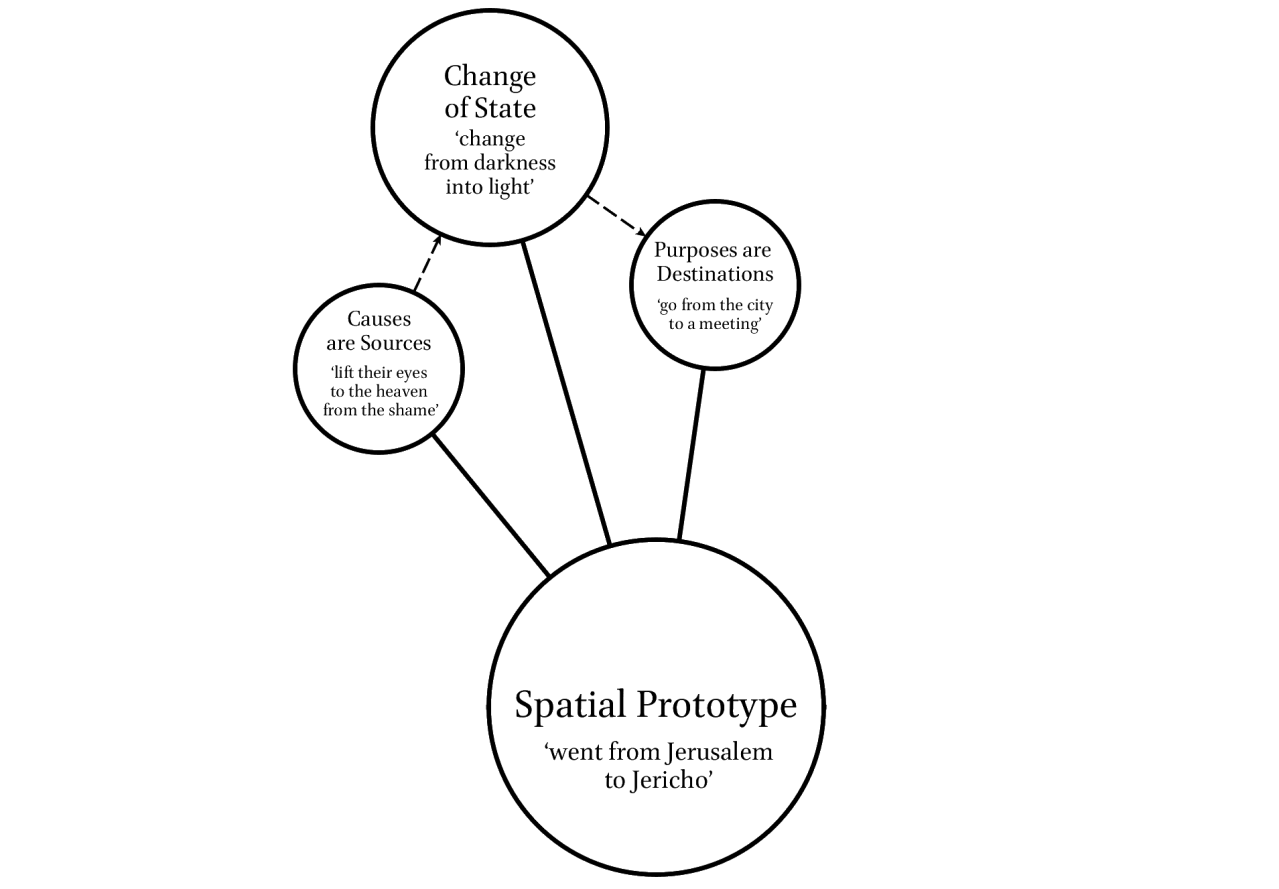

- In the center is the spatial SPG prototype.

- The center line marks three distinct spatial types.

- Extensions from space to abstract domains are above the center line.

- Extensions from space to time are below the center line.

The Source-Path-Goal schema is implicated in our network of constructions. The schema constitutes a dynamic structure made up of related parts that forms a coherent whole: a landmark source, a landmark goal, a path between them, and a trajector that follows the path from one to the other. It is possible then to put into focus, or zoom in on, different aspects of the schema and then map it onto a wide variety of contexts, thus giving a structured coherence to our varied human experiences. Its schematic internal structure (with constituent parts: a source, a goal, a path, and directionality) allows us to highlight different aspects of the structure within a frame: Profiling Source, Goal, or Path.

The prototypical Source-Path-Goal construction

The spatial prototype profiles the trajector’s (TR) movement between a distinct locational source and locational goal. The TR ends up in a different location from where he began, as in example (1).

- a. Ἄγουσιν οὖν τὸν Ἰησοῦν [ἀπὸ τοῦ Καϊάφα] [εἰς τὸ πραιτώριον]

they brought Jesus [from Caiaphas] [to the governor’s residence] (John 18:28).

b. ἔγνω τοὺς ἄνδρας [εἰς γῆν] μεταφέρειν [ἐκ τῆς θαλάσσης]

He decided to transfer the men [to land] [from the sea] (Plutarch, Pompey 28.3).

Here, the trajectors (Jesus and men respectively) undergo and change of location from one landmark location, SOURCE, to another landmark location, GOAL. The spatial prototype profiles (highlights, puts the attention on) the endpoints as denoting the change.

There are also metaphorical extensions that rely on the same profiling pattern, but in different domains of knowledge.

Change-of-state constructions

Thus, change-of-state SPG constructions adapt the schema via the metaphors STATES ARE LOCATIONS and MOVEMENTS ARE CHANGES. The TR’s movement is a path of change from one state to another.

- a. Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ, [διʼ οὗ] ἐκάλεσεν ἡμᾶς [ἀπὸ σκότους εἰς φῶς]

Jesus Christ, [through whom] he called us [from darkness into light] (1 Clement 59.2).

b. ἐνέπεσεν [εἰς ἀρρωστίαν] [ἀπὸ τῆς λύπης]

He fell [into sickness][from despair] (1 Macc 6:8).

Thus, we move from darkness into light, with the SPG schema providing the necessary structure for us to talk about and understand the abstract concept of change in terms of the domain of motion.

Communication constructions

Similarly, the communication domain maps onto the SPG schema as well. The Source is the speaker, sending a message of words along a path to a Goal, the audience. Communication, (speech, writing, etc.) follows a path from Speaker to Addressee.

- Ἰησοῦν τὸν Ναζωραῖον, ἄνδρα ἀποδεδειγμένον [ἀπὸ τοῦ θεοῦ] [εἰς ὑμᾶς] δυνάμεσι καὶ τέρασι καὶ σημείοις

Jesus the Nazarene, a man attested [to you] [from God] with deeds of power and wonders and signs (Acts 2:22).

Here in (3), communication about Jesus (the trajector) travels a path from the first landmark, the source/communicator (God), to the second landmark, the goal/audience, the crowd listening to Peter in Acts 2.

Other constructions, involve profiling the path rather than the endpoints. These include range and iterative path constructions.

Range constructions

Range constructions arise from our ability to map the SPG schema onto static spatial scenes. They do not follow the TR’s motion. Instead, the Source is a starting point for measurement to an endpoint. Because no change occurs, they primarily profile the path rather than the endpoints as in (4) below.

- Spatial

a. κατανεῖμαι τοῖς Λευίταις ὀκτὼ καὶ τεσσαράκοντα πόλεις ἀγαθὰς καὶ καλὰς τῆς τε πρὸ αὐτῶν γῆς περιγράψαντας [εἰς δισχιλίους πήχεις] [ἀπὸ τῶν τειχῶν] αὐτοῖς ἀνεῖναι

Allocate to the Levites 48 good and fair cities and of the land in front of these to mark off and released to them [up to 2000 cubits] [from the walls] (Josephus, Ant. 4.67).

b. καὶ ἐπάταξέν με πληγὴν σκληρὰν [ἀπὸ ποδῶν] [ἕως κεφαλῆς]

He struck me with a severe plague [from head] [to toe] (T.Job 20.6).

The same process may then be applied in both temporal or abstract domains. The flexibility of the SPG schema allows us to understand a variety of measured paths in space, in time, and with abstract concepts.

- Temporal

ὁ βασιλεὺς ἦν ἑστηκὼς ἐπὶ τοῦ ἅρματος ἐξ ἐναντίας Συρίας [ἀπὸ πρωὶ] [ἕως ἑσπέρας]

The king was propped up in the chariot opposite the Arameans [from morning] [until evening] (3 Kgdms 22:35). - Abstract

καὶ εἶπεν αὐτῷ πάντα τὰ γράμματα [ἀπὸ τοῦ ᾱ] [ἕως τοῦ ω̄] μετὰ πολλῆς ἐξετάσεως τρανῶς

And he spoke to him all the letters [from alpha] [to omega] clearly with much interrogation (Inf. Gos. Thom. 6:3).

In both contexts, the preposition landmarks demarcate the boundaries of the situation, whether the measured amount of time (from morning until evening) or the measured quantity of letters (from alpha to omega).

Iterative path constructions

Finally, iterative path constructions expand the schema to a larger scale as a higher order event where the schemas is repeated or extended indefinitely.

The SOURCE and GOAL are deemphasized, as conceptually identical and indefinite place holders for actual referents. Conceptually identical landmarks make it possible to put the SPG schema back-to-back, and you get an iterative path as we walked from house to house in our neighborhood. The same cognitive pattern allows us to do the same with time. In example (7), we see how the atelic verb “tip” with two demonstrative pronouns.

- ἔκλινεν [ἐκ τούτου] [εἰς τοῦτο]· πλὴν ὁ τρυγίας αὐτοῦ οὐκ ἐξεκενώθη, καὶ πίονται πάντες οἱ ἁμαρτωλοὶ τῆς γῆς

He tipped {the cup of unmixed wine} [from this way] [to that way]; yet its dregs were not emptied out, and all the sinners of the earth will drink it (Psalm 74:9).

Using the same temporal landmark, we can talk about how often repeated activities take place in our lives. In example (8) we see how some things we do from day to day (singing to the Lord in 1 Chron 16:23). Others from month to month (whole burnt offerings in Num 28:14) or year to year (as the cycling the seasons evinced by the trees in Enoch 5:1-2).

- Temporal

a. ᾄσατε τῷ κυρίῳ πᾶσα ἡ γῆ, ἀναγγείλατε [ἐξ ἡμέρας] [εἰς ἡμέραν] σωτηρίαν αὐτοῦ.

Sing to the Lord, all the earth; announce his deliverance [from day] [to day] (1 Chron 16:23).

b. τοῦτο ὁλοκαύτωμα μῆνα [ἐκ μηνὸς] [εἰς τοὺς μῆνας τοῦ ἐνιαυτοῦ]

This is the monthly whole burnt offering [from month] [to the months of the year] (Num 28:14).

c. καταμάθετε καὶ ἴδετε πάντα τὰ δένδρα…[ἀπὸ ἐνιαυτοῦ] [εἰς ἐνιαυτὸν] γινόμενα πάντα οὕτως

Observe closely and see all the trees…they all continue on in this way [from year] [to year] (Enoch 5:1-2).

Abstract iterative paths like “the people went from evil to evil” rely on the same schematic pattern in example (9).

- Abstract

καὶ ἐνέτειναν τὴν γλῶσσαν αὐτῶν ὡς τόξον· ψεῦδος καὶ οὐ πίστις ἐνίσχυσεν ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς, ὅτι [ἐκ κακῶν] [εἰς κακὰ] ἐξήλθοσαν, καὶ ἐμὲ οὐκ ἔγνωσαν

And they bent their tongue like a bow; falsehood and not faith grew strong upon the land, for they went [from evil] [to evil], and they did not know me (Jer 9:3).

People who go from evil to evil, can always be counted on to be up to no good, regardless of the current evil behavior. Because of their character, you can always be sure that they will move on to the next evil behavior soon enough.

Summary

In all cases, the SPG schema, with its internal structure and constituent parts provides a schematic basis for understanding a whole variety of different event types in human experience from concrete events to the most abstract ideas. These are then all realized in Greek with family of language-specific constructions. It is a powerful cognitive pattern that we use every day to understand the nature of our world.

We conclude by emphasizing one final characteristic of grammatical constructions: Constructions are interrelated, something we see in detail here. Adele Goldberg calls them “a highly structured lattice of interrelated information” (Goldberg 1995, 5). It should come as no surprise, then, that constructions illustrate prototypical structures. Because they are form-meaning patterns, they readily schematize across domains.

As a result, they also form networks of relationships and hierarchies. The way they extend across domains and form relationships guides their interpretations when creative or novel instances of language use appear. Speakers/hearers understand creative and novel usages because they naturally integrate into the existing network.

Bibliography

Benware, Wilbur A. 2000. “Romans 1.17 and cognitive grammar.” The Bible Translator 51:3, 330-340.

Benware, Wilbur A. 2006. “Second Corinthians 3.18 and Cognitive Grammar: apo doxes eis doxan.” The Bible Translator 57:1, 45-51.

Brenda, Maria and Jolanta Mazurkiewicz-Sokołowska. 2022. A Cognitive perspective on spatial prepositions: Intertwining networks. HCP 74. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Clausner, T. C., and W. Croft. 1997. “Productivity and schematicity in metaphors.” Cognitive Science 21 (3): 247–82.

Croft, William. 2022. Morphosyntax: Constructions of the world’s languages. Cambridge Textbooks in Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

Danove, Paul L. 2005. A Grammatical and exegetical study of New Testament verbs of transference: A Case frame guide to interpretation and translation. Library of New Testament Studies 13. New York: T & T Clark.

Danove, Paul L. 2015. New Testament verbs of communication: A Case frame and exegetical study. Library of New Testament Studies 520. New York: Bloomsbury T & T Clark.

Delbecque, Nicole and Bert Cornillie. 2007. On interpreting constructional schemas: From action and motion to transitivity and causality. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Dirven, Rene. 1995. The Construal of cause: The case of cause prepositions. In John R. Taylor and Robert E. MacLaury (eds.) Language and the cognitive construal of the world, 95-118. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Evans, Vyvyan. 2019. Cognitive linguistics: A Complete guide, 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP.

Goldberg, Adele E. 1995. Constructions: A Construction grammar approach to argument structure. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Goldberg, Adele E. 2006. Constructions at Work: The Nature of generalization in language. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Goldberg, Adele E. 2019. Explain me this: Creativity, competition, and the partial productivity of constructions. Princeton: Princeton UP.

Hampe, Beate and Joseph E. Grady 2005. From perception to meaning: Image schemas in cognitive linguistics. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Hoffmann, Thomas. 2022. Construction grammar: The Structure of English. Cambridge Textbooks in Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

Johnson, Mark. 1987. The body in the mind: The bodily basis of meaning, imagination, and reason. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Lakoff, George. 1987. Women, fire, and dangerous things: What categories reveal about the mind. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Lakoff, George and Mark Johnson. 1999. Philosophy in the flesh: The Embodied mind and its challenge to western thought. New York: Basic Books.

Langacker, Ronald W. 1987. Foundations of cognitive grammar: Vol. 1 Theoretical prerequisites. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Lewandowska-Tomaszczyk, Barbara. 2007. Polysemy, prototypes, and radial categories. In Dirk Geeraerts and Hubert Cuyckens (eds.), Oxford handbook of cognitive linguistics, 139-169. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Luraghi, Silvia. 2003. On the meaning of prepositions and cases: The expression of semantic roles in Ancient Greek. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Norvig, Peter and George Lakoff. 1987. Taking, a study in lexical network theory. Proceedings of the 13th Annual Meetings of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, 195-206.

Talmy, Leonard. 2000. Toward a cognitive semantics. Vol 1. Concept Structuring Systems. Cambridge: The MIT Press.